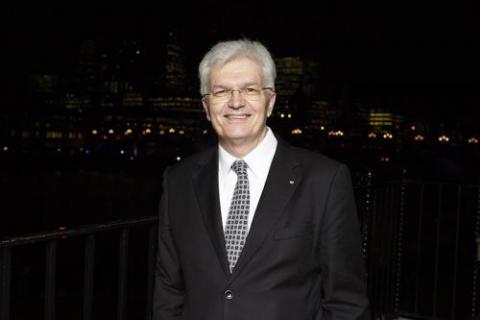

We asked panel member, public policy expert and Vice-Chancellor at the University of Melbourne Professor Glyn Davis a series of questions about this review and the Australian public service.

Read on to hear why he joined the review and explore some of the strengths and challenges in front of us.

What was the appeal for you to work on the independent review of Australia’s public service?

‘It is time to serve your country again’ said Martin Parkinson, the head of the Prime Minister’s department when he called with David Thodey to suggest I join the review. It is hard to say no to such an appeal!

There are, of course, many other good reasons for accepting – a lifelong engagement with public administration as scholar and practitioner, a strong commitment to the centrality of the public service in good government, and an opportunity to close a circle.

When a doctoral student at the ANU, I took leave from the thesis to work as a researcher for the Reid Inquiry into Commonwealth Administration.

This was commissioned by Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser in 1982 and reported to Prime Minister Bob Hawke early in 1983. The chance to return to the field 35 years later and see how much has changed and what lessons were learned, is too good to miss.

What similarities or differences do you see between the Australian public service and the organisation you manage — the University of Melbourne?

Any 2 large organisations will have much in common, particularly around administrative processes.

Yet the defining feature is always strategy and here are significant practical differences between the University of Melbourne and the Australian public service.

These include relative stability – the university sector has grown hugely but maintained its identity and basic organisational features. By contrast, there has been radical transformation in many sections of the APS, including contracting out functions once considered core to a public service.

In your opinion, what does the Australian public service do really well and need more of in the future?

At its best, the APS helps guarantee some continuity in Australian national life. It is the institution that reflects and delivers our shared aspirations.

Specific programs and structures respond, as they must, to political leadership but much of what the Australian public service does endures across administrations.

So our national interests might change over time, along with the foreign minister. Yet the expertise and intellectual capabilities embedded in a department of foreign affairs and trade ensures the nation can be represented with confidence internationally, and build programs domestically to serve and support whatever government is chosen by the people. Such expertise to act in the world, once lost, is very difficult to replace.

What do you see as the single biggest challenge for Australia’s public service in 2030?

Much service delivery may be automated by 2030, but the hard work of thinking about problems, and working systematically through a policy cycle based on evidence and experience, will remain core to the APS. Hence maintaining and building further the nation’s policy making capacity is our largest challenge now and in 2030.

What has been the most interesting thing you’ve discovered about the Australian public service through the review?

The passionate commitment to serving the public by staff at every level is no surprise but it has been reinforced through face-to-face and written consultations.

So too the worry about lost capabilities. The Review has heard concerns about the hollowing out of policy expertise in the drive to efficiency. Clearly there is an important balance here needing close attention.

Is there something you’d suggest people read or listen to?

Recent Policy Shop podcasts have explored two issues subscribers might find of interest:

- The Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Dr Martin Parkinson reflected on his career covering Australia’s major economic reforms of the 80s and 90s, establishing the first Department of Climate Change and forming policy amidst today’s 24-hour news cycle. Listen to Does government get the right advice.

- Patricia Rogers, Professor of Public Sector Evaluation at the Australia and New Zealand School of Government (ANZSOG) and Nicholas Gruen, CEO of Lateral Economics examine how we can improve public policy in Australia. In particular a proposal for a new model for evidence-based policy is examined.

Finally, subscribers may also be interested in reading the 2015 paper in the Australian Journal of Public Administration on the role of senior officials in intergovernmental outcomes.